The theory of innovation, part 3: Schumpeterian Waste

How innovation works, and how you should design your business around it

This is a weekly-ish newsletter from Al Cottrill. It’s mostly an informal outlet for the theory and esoterica that underpins our practice. We hope you find it interesting.

First, apologies for the slight delay in getting this out. I’ve been moving house all week…

So this is probably my favourite concept in innovation. In all honesty, the previous two notes were just building the foundational concepts supporting this one. But I genuinely believe this concept is the key reason behind the failure of most corporate innovation initiatives.

So here’s my thesis. From all my work in innovation across the years, I've come to the following conclusion: Organisations don't fail at innovation because they're bad at the 'innovating' bit. That is, taking an idea and building out a product/service/business concept (though there’s still a lot of room for improvement in designing viable businesses). Instead they're bad at the bit around that: managing the investment in innovation.

But to wind back a bit, the last two notes introduced two principles.

First, that innovation has a common structure to it: the proliferation and pruning of options; the emergence of a dominant, viable design; and the failure of competing alternatives.

And second, that the reason it looks like this is because it’s a class of evolutionary system. Evolution is a general-purpose process for navigating uncertainty and creating innovative new forms. And what we’re seeing in this proliferation and pruning is the evolutionary algorithm at work – differentiation of designs, selection of viable solutions, and amplification of the winners.

But this note is about the third principle of innovation systems. And the core of this is a little idea called ‘Schumpeterian Waste’. So here we go…

Understanding waste

Perhaps the most interesting characteristic of any evolutionary system is that they are wasteful. That is, while they’re effective at finding viable designs under uncertainty, they’re also very ‘inefficient’ in doing so.

Hopefully the reason is obvious based on what I've shared so far: innovation systems work through a process of proliferation of options, refinement based on feedback, scaling of viable options and the failure of non-viable designs. And this trialing, obviously requires ‘erroring’.

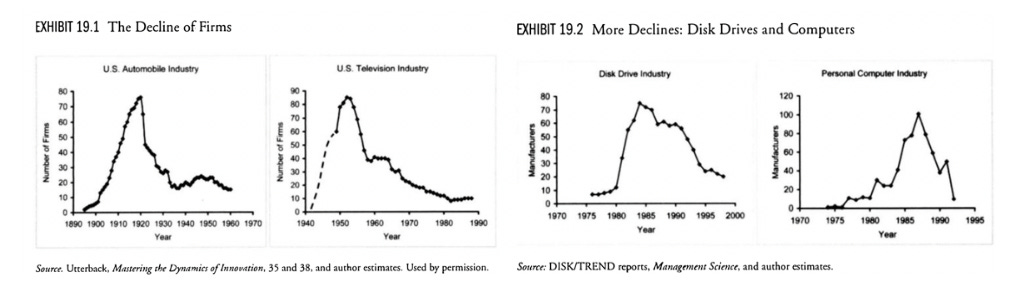

Essentially, in order to find something viable-enough under uncertainty, you need to invest a lot in things that won’t end up working. So evolutionary systems go through their phases of ‘proliferation’ and massive over-production of options relative to the final number of them that survive (seen below in the huge number of entrants vs. survivors). It’s a massive ‘search’ process, experimenting to reduce the uncertainty on what to find a design that works.

And it’s this ‘wastefulness’ that is a fundamental attribute of any effective innovation system.

Not Waste, Want Waste

So the ‘word’ waste is a bit misleading really, because the point is it’s not waste.

If we take the bicycle example from my first note, the overproduction of options seems wasteful because it involves spending a lot resources on a lot of things that don’t work.

And any observer (perhaps your CFO) is likely to look it and ask “this seems crazily inefficient, do we really need all these failures”. (And you see it all the time when people look at any startup industry and say ‘look at all these failures, it’s nonsense’.)

But what you get off the back of all this failure is a much greater likelihood of a viable outcome. Or in the language of evolution, a more ‘fit’ design.

We can think about this in probabilistic terms. The more I invest in search, the more options that are tried, the more variations explored, the greater likelihood I find a design that works – or one with a greater probability of success. The flipside of this is the less I explore, the less design variants I test, the more quickly I converge, the earlier I commit to a single design, the lower the probability is that it will be the ‘fittest’ design out there (or even viable at all).

So while innovation systems look inefficient because of all the failures in them, it’s a required part of them being effective.

And instead of ‘waste’, we should think of these failures as ‘the inevitable byproduct of trial and error inherent in an innovation system’. Or, failures as ‘investment in increasing our probability of success’.

When framed that way, you start to see the link between failure and success probability… but we’ll get to that in a bit.

Schumpeterian Waste

Eric Beinhocker (who wrote The Origin of Wealth I referenced last week) makes the same point about the inefficiency of these systems here:

The orthodox economic view holds that capitalism works because it is efficient. But in reality, capitalism’s great strength is its problem-solving creativity and effectiveness. It is this creative effectiveness that by necessity makes it hugely inefficient and, like all evolutionary processes, inherently wasteful. Proof of this can be found in the large numbers of product lines, investments, and business ventures that fail every year

Venture Capitalist Bill Janeway calls these failures (and the human, physical and financial capital deployed in their pursuit) 'Schumpeterian waste', after the great innovation economist Joseph Schumpeter:

At the frontier, economic growth has been driven by successive processes of trial and error and error and error: upstream exercises in research and invention, and downstream experiments in exploiting the new economic space opened by innovation. Each of these activities necessarily generates much waste along the way: dead-end research programs, useless inventions and failed commercial ventures. In between, the innovations that have repeatedly transformed the architecture of the market economy, from canals to the internet, have required massive investment to construct networks whose value in use could not be imagined at the outset of deployment. This is the messy environment through which Schumpeter’s “gales of Creative Destruction” sweep. This is why an innovation system is required that can tolerate what I call necessary Schumpeterian Waste.

Think of all the prototypes, bicycles, fintechs, synapses and species that are discarded – and all of investment behind them. This is the Schumpeterian waste of innovation.

Tolerating waste

Janeway in his (excellent) book Doing Capitalism in the Innovation Economy makes what is perhaps the fundamental point of all of this:

“The innovation economy turns on the ability of the economic system to tolerate waste”

Paraphrased, he’s saying that "if your innovation system can't tolerate waste, it won't be effective".

And he goes on:

"Those who hold the organisation to rigorous criteria of efficiency in the allocation of resources… inhibit toleration of the “Schumpeterian waste” inherent in the operation of Innovation"

So what’s going on here?

Economics is obsessed with efficiency. And with that, so are businesses.

Let’s look at it this way: In normal business, if you deploy MORE capital than you need to, i.e. if there is waste in the system, you will generate lower returns.

So ‘bad’ waste is unproductive capital. In an economic context, this is things like unemployment and shuttered factories. In a firm context, this is things like ‘unnecessary’ headcount and expenditure, failed projects, project over-runs and over-investment. (Janeway calls this second type ‘Keynesian’ waste, named for Keynes’s arguments about the deadweight loss of unemployed human and physical capital).

So to maximise returns, the bias of any businesses will be to drive to efficiency. That is, strip any investment out that isn’t directly contributing to the outcome. In short “can you do it cheaper and faster”.

But in any economic system, we also have the ‘good’ Schumpeterian Waste that is required as part of any innovation system.

To contrast the above: in innovation, if you deploy LESS capital than you need to, if try to remove waste from the system, you will generate lower returns.

While innovation systems are still l optimising for return on investment, they have all sorts of Schumpeterian waste in the system - investment in speculative bets, failed investments, dead-end exploration routes – that are required for it to function effectively.

The problem is this: to the outside observer – they look the same. That is, businesses’ traditional measurement and funding systems can’t tell Schumpeterian waste from Keynesian waste. Failure is failure, waste is waste. All of it is bad, and the intrinsic motivation is to reduce it.

That is, most organisations are built, very specifically to not tolerate waste.

This is why Janeway calls it ‘waste’ even though it is not waste. He is calling our attention to the fact that all failure isn’t failure, all ‘unproductive’ capital isn’t unproductive.

A failure to fail

Schumpeterian Waste is hard to really get your head around.

That is, the waste is the fuel of the innovation system. It’s the oxygen. It’s the productivity driver. It’s the ‘inevitable byproduct’. It’s as important as the successful initiatives to generating the returns.

In turn, it says that a blunt drive to make an innovation system more efficient will have the perverse effect of making it less effective. The waste and the returns form a single, irreducible whole*. And this makes the traditional approaches to project and portfolio investment, management, measurement, and governance incredibly harmful to a successful innovation system.

And this is the suboptimal equilibrium most organisations find themselves in: They place less bets than they need to; they don’t allow redundancy across their options; they measure and manage individual initiatives to success rather than the system as a whole; and they look at the failure as negatives and apportion blame.

So back to my original thesis at the start of this note. Organisations are not set up to tolerate the Schumpeterian Waste required of successful innovation. And the effect of this is to suffocate their innovation efforts, limiting the oxygen of investment in exploration they require (and the time horizons for success) to deliver the required returns.

And 2 years into their innovation initiative, never having given the system the oxygen it needed to succeed, they see only a string of failures and underwhelming results and shut it down.

No matter how good they are at the innovating bit itself, it is strangled by the failed investment system around it.

Failing successfully

To put it directly: The ability to tolerate waste is the defining characteristic of successful innovation systems.

One organisation that has done this with phenomenal success is Amazon. This isn’t a coincidence, Bezos talks openly about the dynamics I’ve described so far, and the ability of Amazon to deliberately tolerate waste. Here is his shareholder letter from 2016:

“One area where I think we are especially distinctive is failure. I believe we are the best place in the world to fail (we have plenty of practice!), and failure and invention are inseparable twins. To invent you have to experiment, and if you know in advance that it’s going to work, it’s not an experiment. Most large organizations embrace the idea of invention, but are not willing to suffer the string of failed experiments necessary to get there.”

In essence, Bezos has internalised these ideas at Amazon, and built it as an innovation approach founded on the principles of inefficient evolutionary system. Here he is in more detail in an interview with Business Insider:

Again, one of my jobs is to encourage people to be bold. It’s incredibly hard. Experiments are, by their very nature, prone to failure. A few big successes compensate for dozens and dozens of things that didn’t work. Bold bets — Amazon Web Services, Kindle, Amazon Prime, our third-party seller business — all of those things are examples of bold bets that did work, and they pay for a lot of experiments.

I’ve made billions of dollars of failures at Amazon.com. Literally billions of dollars of failures. You might remember Pets.com or Kosmo.com. It was like getting a root canal with no anesthesia. None of those things are fun. But they also don’t matter.

What really matters is, companies that don’t continue to experiment, companies that don’t embrace failure, they eventually get in a desperate position where the only thing they can do is a Hail Mary bet at the very end of their corporate existence.

As painful as it is to fail, it’s an essential part. The amazing thing here is how Bezos has built the entirety of Amazon around these principles - it is Amazon as evolutionary system (rather than just an innovation function off the side).

Repeating Markides point from his research I included last week:

“[Successful strategic innovators] have purposefully created internal variety (even at the expense of efficiency) and then allowed the outside market to decide the winners and losers. Thus, within many strategic innovators is the harmonious coexistence of often conflicting features (i.e., variety) that are continuously tested in the market and, if found wanting, are eliminated without too much debate.”

But as we’ve pointed out, innovation systems exist at multiple scales.

The same dynamics are true for Silicon Valley, and its culture of ‘failure is ok’. At a industry agglomeration-level, it is essentially a system that can tolerate waste without punishment.

And here's Nassim Taleb, in his book, Antifragile, with the same insight regarding nation-level innovation:

“Like Britain in the Industrial Revolution, America’s asset is, simply, risk taking and the use of optionality, this remarkable ability to engage in rational forms of trial and error, with no comparative shame in failing again, starting again, and repeating failure.”

Whenever we look around and see an effective innovation system, whether that is at the level of an organisation (Amazon), an industry agglomeration (e.g. Silicon Valley), or a whole economy (Britain in the Industrial Revolution or post-war America), we see the same dynamics: rational trial and error and toleration of the associated waste.

To re-emphasis: Schumpeter, Janeway, Taleb, Bezos, Markides (we need some diversity here) are all saying the same thing: for innovation to be successful, the system needs to tolerate waste.

But as you’re probably well-aware, that’s not how most businesses are set up today.

In summary…

The thing I love about the concept of Schumpeterian Waste is it’s so counter-intuitive.

We have a strong tendency to want only the successes - to attempt to increase the wins and reduce the failures. But the concept of Schumpeterian Waste tells us that the important part of an innovation system is the waste itself, that it has an essential role in it.

But importantly it also tells us that while all unproductive capital may look the same, within it we have good waste and bad waste. And that in organisations’ fundamental drive toward efficiency and reduction of bad waste, they will likely also reduce the good waste required for effective innovation.

In essence, if you fund, measure, govern innovation in the same way – or even expose it to the core business without careful consideration, you will likely suffocate it. No matter how good you are at the actual innovating part of innovation.

So for innovation to be successful, you need to explicitly design the system to tolerate it. And to protect it from the business which funds it.

This, to me, is the fundamental reason behind we need to separate the two worlds. The world of the core business, of execution, efficiency and optimisation. And the world of innovation, evolution and Schumpeterian waste. Everything else - culture, process, practice - is irrelevant until we have built a system that can tolerate waste.

So next week I’m going to get into what this all means for why corporate innovation efforts tend to get this so fundamentally wrong; the symptoms (and why Innovation Directors have short tenures); and start to get to the outlines of what a good innovation system looks like.

And if you made it here, thanks for reading this far. If you missed the previous editions you can read them here and here. If you’d like to ask a question, use the comments below. And if you’re enjoying it, please share to anyone else interested.

Thanks,

Al

*The hard part here is that you can still have Keynesian waste in an innovation system, for example if you let an initiative run when it should have been killed earlier. The hard part is recognising the difference. But ‘how much waste do I need overall’ and ‘how do I make the decision when to stop investing’ are questions I’ll address later.

**I should note that the dynamics I talk about here at the ‘innovation’ level apply as much to the larger strategic options a business might be pursuing overall, but that’s for another post.

End notes

Once you have these patterns in your mind, you start to see them everywhere:

And if you want to go a little deeper on Schumpeterian waste, I recommend Bill Janeway’s book, Doing Capitalism in the Innovation Economy.

But here he is explaining some of his ideas:

Hello, I like how you frame Schumpeterian waste. One thing he and Keynes had in common is that while rational they acknowledged there is irrationality that drives innovation. Animal spirits in Keynes' case and the entrepreneur's spirit in Schumpeter's. But, they stopped there and slid back to homus economus thinking. I agree not tolerating waste stops innovation. Though what is curious to me is in many companies how much bad waste there is, of good innovations (programs, concepts, incubators, acquisitions, green shoots, etc) that should proceed but don't due to irrational rationality. I'm making a different point, but it is an area I'm researching on the psychodynamic that get in the way of companies spending billions, with the right capabilities, doing the right things but not realizing their full innovation potential. This happens at Amazon too, BTW, they are just much better at balancing to good waste. If you're interested in my research you can learn more here and sign up to my newsletter along the way https://www.brettmacfarlane.com/research

Thanks for your newsletter.